Compensation Gone Bad

Many of us celebrate Thanksgiving and the constellation of family, friends, food, and fun that go along with the holiday. Also for many of us, the fun part of the equation involved alcohol (or maybe alcohol is tied to the family part if you don’t get along.) Either way, the day before Thanksgiving is often referred to as Blackout Wednesday given it is typically a bigger drinking day than New Year’s Eve or St. Patrick’s Day.

When we drink, our brain is impaired. Now, I’m not about to admonish anyone’s consumption proclivities. I’m more interested in the progression, and relatedly our own perception, of said impairment and how the concept applies elsewhere.

Even though a single drink is enough to contribute to impairment, we don’t immediately take notice of the impairment. Our brain is compensating in such a way that we may not report feelings of inebriation until we are well past reasonable control of our motor functions. Some people describe the feeling as “hitting a wall” when perception of impairment catches up to the reality of its intensity. Although that’s the way we may feel it, it’s not how it actually progresses. We are moving along a continuum of impairment the entire time we are drinking but our brain is doing its best to compensate until it can’t anymore.

Depression seems to present itself in a very similar way.

By the time someone decides to enter the mental health system or seek help (if they do at all), it is usually not until they are at the depression equivalent of being blackout drunk. However, the difference with being drunk is that it passes with hydration, time, and rest in a reasonably quick period of time. That’s not true of depression. Unfortunately by the time someone with depression reaches the intersection of being able to perceive it, they turn to self harm or attempt suicide. In fact, the average time from onset of symptoms to treatment is 11 years.

How can we fix this? How can we be the depression “designated drivers” for people? How can we meet people earlier in their mental health journey?

It’s important that we think deeply about these questions and build tools to measure early indications of mental health deterioration so that we can better understand which interventions work the best for specific types of people. There is no shortage of effective treatments for depression. There is a massive shortage of effective measurements, which is where the attention needs to concentrate in order to fix the problem.

Therapists and clinicians act as the primary depression measurement tool today. They are trained “designated drivers” who are in effect conducting mental health sobriety tests with patients to determine the presence and level of depression. Patients give them data, typically in the form of natural language via discussions, and clinicians interpret the language use with their processor (brain). The problem with that approach will always be its inherent lack of scalability. There is simply not enough practicing clinicians to see the volume of people who are in need. There is barely enough bandwidth to keep up with people who already seek help, let alone for the nearly 50% who go undiagnosed or never seek help at all.

Now what? Well, if we think about how to take the processor being used for measurement today (the therapists brain) and the common input it is measuring (natural language, among other cues) one can imagine creating the “silicon” twin of the biological processor and coupling it with an ingest function of the input (being natural language from a patient).

A software tool trained to interpret inputs like a therapist that is not limited by the constraints of a biological processor would be able to exponentially scale important capabilities like screening, measuring, and risk stratification.

That’s the idea behind eli (a software tool that uses deep learning to measure written content against a mental health taxonomy). By turning written word (and spoken word in the future) into a machine-readable biomarker for wellbeing, mental health measurement can be done at scale as low-friction, sub-clinical assessments. Individuals and care providers can then focus on delivering the right care at the right time which leads to shortened time to diagnosis, reduced costs, and improved outcomes.

We are all familiar with physical fitness wearables that give us information like daily steps taken so that we can improve our physical health. It’s time we have the equivalent for our mental health.

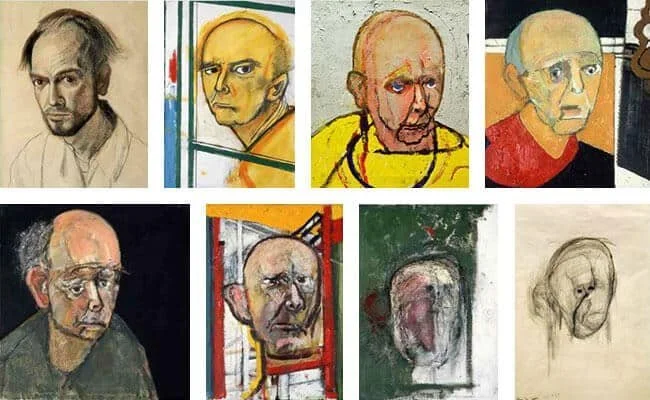

PS - the image above is a collection of self-portraits from William Utermohlen. In 1995, William was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Over the course of several years post-diagnosis, his self-portraits were his way of documenting the gradual decay of his mind. I thought it was another appropriate way to think about our relationship with our own impairments. To him, each painting was a snapshot of how he was experiencing reality, not necessarily being aware of the impairment brought on by his disease